Okay, this is somewhat of a metaphorical post. Still, I expect that you can apply the concepts of this story to your own “mountains” that you need to climb and summit.

A few weeks ago, I backpacked with my friend Bill. What’s great about going into the wilderness for a few days with Bill (in this case, four days) is that we communicate so well, respect each others needs, and consider them throughout the trip. This kind of deep communication becomes especially pointed living in the woods when your kitchen and bedroom are in the pack on your back.

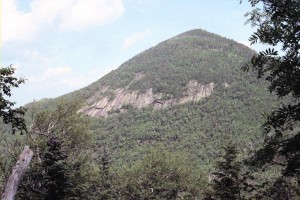

This trip, our goal was to summit four of the forty-six 4,000-foot peaks in New York’s Adirondack park. (Actually, there are only 43 such peaks. Apparently, past climbers couldn’t measure very well, but history dictates compliance with their inaccurate measurements.) Four days, 32 miles, 12,000 feet of elevation gain, fifty-pound packs, all planned with a guide book last published seven years ago—an eon for the Adirondacks where landscape-altering storms are the norm.

This trip, our goal was to summit four of the forty-six 4,000-foot peaks in New York’s Adirondack park. (Actually, there are only 43 such peaks. Apparently, past climbers couldn’t measure very well, but history dictates compliance with their inaccurate measurements.) Four days, 32 miles, 12,000 feet of elevation gain, fifty-pound packs, all planned with a guide book last published seven years ago—an eon for the Adirondacks where landscape-altering storms are the norm.

While we had a general idea of the summiting trails, we also knew that routes and conditions would be different—in two cases, markedly different as it turned out—from descriptions written at least seven years ago, and probably eight. We knew this going in, and we knew that we would be trying to get the latest conditions, from whoever we crossed paths with, always an eye-opening and trusting endeavor.